Section 1: Chocolate’s Roots

Introduction

This first section of the exhibit highlights the environmental issues and ancient Mesoamerican history intertwined with chocolate. Highlights include two artifacts made by students at the LCC out of recyclable materials like a pop can, paper bags, and a wire clothes hanger. A Maya drinking vessel depicts chocolate being served in a spiritual ceremony and ancient hieroglyphic imagery, while a replica cacao tree serves to introduce viewers to the plant behind the product. Theobroma cacao is a sensitive tree, which grows best in the complex rainforest ecosystem most threatened by global issues of climate change and deforestation. Integral to the mission of the LCC is to draw out connections between cultural sustainability and environmental sustainability, which is really explored through the themes of this section.

a

Theobroma Cacao Tree Replica

Theobroma Cacao Tree Replica

Paper Mache; Chicago, USA

LCC Staff, 2015

Cacao Trees in the Rainforest

Source: SantaBarbaraChocolate.com

This replica was made by students at the UIC Latino Cultural Center out of recycled materials, but real cacao trees can grow up to 40 feet tall! The Theobroma (“Food of the Gods”) cacao tree is originally from the rainforests of Central and South America, where shade, heat, and humidity are essential for this sensitive species. Tiny midge flies pollinate the tree’s white flowers, which then fruit into large multicolored cacao pods.

Today, chocolate sales expand around the world, but the areas it can grow are actually shrinking. Climate change and devastating deforestation are threatening the future of the cacao plant, along with many other essential products from the rainforest. This important ecosystem is the source of 80% of foods used by the developed world, from avocados to essential medicines. Be mindful buying tropical resources to help protect the rainforest for future generations.

Le Cacao Poster

Le Cacao poster

Paper; Paris, France

Deyrolle family, 1831-1895

The Deyrolle family of natural historians created this poster as a teaching tool over a hundred years ago to show the process from tree to chocolate. You can see a cacao tree on the top right of the image, with fruit pods growing from the trunk. In the top left of the image, a cacao pod has been cracked open to reveal a core of seeds, enveloped in milky pulp. The pulp itself is sweet, and it has also been used in traditional recipes, such as Nicaragua’s famous drink, Pinolillo.

Maya Vessel Replica

Maya Vessel Replica close-up

Paper Mache; Chicago, USA

Honduras, 250-900 AD

Kerr Collection Rollouts, 2002

Aztec woman pouring chocolate

Source: WorldStandards.eu

Codex Tudela, Madrid 1553

The Maya loved their chocolate, and they created special cups from which to drink. Hundreds of vessels like this replica have been found throughout Central America, decoded by archaeologists who can read the ancient hieroglyphic writing. Look through the magnifying glass to see the glyph, which looks like a fish. This was one way of writing the Maya word for chocolate. People would grind cacao nibs into a paste and mix it with hot water and spices. The heat from the water caused the chocolate to separate into layers as it settled. Mesoamericans would then pour the drink between two cups to keep it mixed, producing a frothy delicacy almost like a latte today! To the Maya, the spirit of the chocolate could be found in the froth. The Aztec woman in the image to the right was documented doing the same traditional practice many years later. This drink was especially important among the elite in spiritual ceremonies like the scene pictured on the vessel. The Toltec and the Aztec also used cacao seeds as money!

Cacao seeds and Molcajete

Cacao Seeds

Yucatan, Mexico 2014

To the ancient Mesoamericans, this was a big pile of money! Cacao seeds were used as currency, earned by workers as wages and traded far and wide for other materials. In this display you’ll see dried seeds on the left and roasted ones on the right, also known as “nibs” by chocolatiers today.

Crack open a cacao pod and you’ll find these seeds nestled in a milky pulp. Together seeds and pulp are exposed to the air for several days to ferment. This chemical process releases key enzymes. The seeds are spread out to dry in the sun for about a week, then delicately roasted.

At this point they’re usually shipped overseas for the next round of processing. The cacao nibs are ground down in a high heat, where the fat (cocoa butter) is separated out from the cocoa powder. The powder is then easier to work with, and it’s sometimes sold on its own as unsweetened baking chocolate. Meanwhile, the cocoa butter is alkalized so it will remain suspended in liquid longer and added back to the powder with extra ingredients like milk, sugar, and spices. Chocolate is then poured into molds, dried, packaged, and shipped to a store near you! Each stage of the process contributes to the rich flavors we know and love.

Molcajete and Tejolote

Basalt Rock; Mexico 1980

This traditional Mexican version of mortar (molcajete) and pestle (tejolote) are used to grind various foods like spices and chiles. Chocolate is traditionally ground using a much larger and heavier stone tool called a metate, which is long and flat rather than round. A metate wouldn’t have fit very well in this delicate glass case, but this molcajete can be useful for chocolate in other ways. Mole, a savory Mexican sauce, is usually made with a chocolate base, but its many other spices can be ground using a tool like this one.

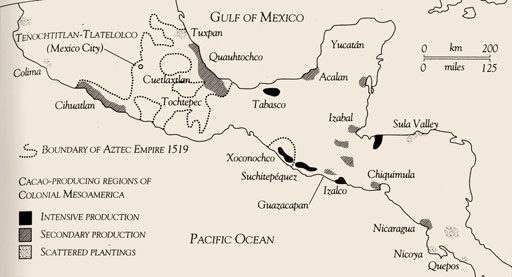

Map of Central American chocolate-growing

Map of Central American chocolate-growing regions

Source: Chocolate Class Cacao Transformed

The cacao tree first developed in the Amazon rainforests of South America relatively recently in around 15,000 BC. Indigenous people initially bred the tree for the sweet pulp in its pods, rather than the cacao seeds themselves. People traded the plant with neighboring communities over thousands of years. By the time of the Olmec civilization (approximately 1500 BC) cacao was likely grown from today’s Peru in the South to Mexico in the North. Chocolate evidence has even extended as far north as today’s Arizona and New Mexico. You may be wondering what this rainforest plant was doing all the way up in the desert. Archaeologists see this as evidence of extensive trade throughout the Americas. Chocolate has been a transcontinental product for thousands of years!

Molinillo

Molinillo

Wood; Mexico

2009

This wooden device is held between two palms and twisted back and forth to stir hot chocolate. Raw hot chocolate naturally separates, with a fatty layer of cocoa butter floating to the top. The Aztecs usually poured chocolate between two cups to keep it mixed and frothy, while Europeans usually stirred with a spoon. As indigenous and Spanish cultures blended into a more Mexican identity, the Molinillo was invented for the very same purpose.

Are there particular utensils used for chocolate in your culture?

Tell us about it using #chocostorylcc or submit a story on our home page

Choco-Stories’ Roots

nav